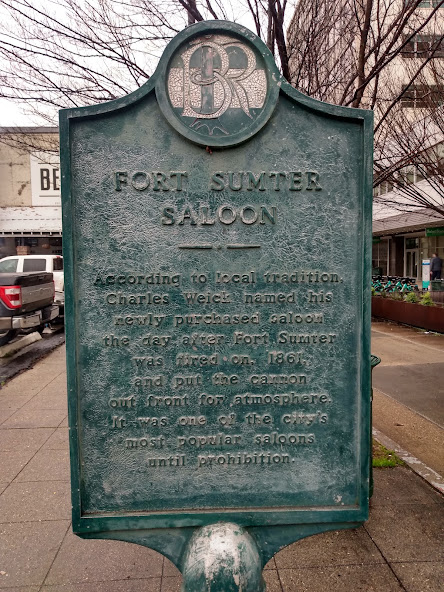

It reads: "FORT SUMPTER SALOON - According to local tradition, Charles Weick named his newly purchased saloon the day after Fort Sumter was fired on, 1861, and put the cannon out front for atmosphere. It was one of the city's most popular saloons until prohibition."

From the text, one might assume that the mysterious object in question is the cannon that used to stand in front of Weick's old Fort Sumpter Saloon. For decades, numerous books have been written about the history of Baton Rouge, and all of them refer to this cannon as the one that was once displayed in front of Weick's famous watering hole—after all, the sign states as much.

Many people have accepted this explanation, but it doesn't clarify how the cannon became embedded in the pavement. The real story is far more intriguing and highlights that the historical marker isn't entirely accurate.

According to John Sykes, the executive director of BREC's Magnolia Mound, who is working on a book about downtown Baton Rouge landmarks, the original location of Weick's saloon—where the cannon was displayed—was actually at Third and Main, not at its current site at Third and Laurel. So, this cannon is not the same as the one associated with Weick's saloon.

In reality, this is a British cannon from before 1779, used to defend their fort in Baton Rouge. In 1779, that fort fell to Spanish forces and was renamed Fort San Carlos. In 1810, the fort was taken over by British and American settlers before eventually being controlled by the U.S. Army.

However, this still doesn’t explain how a pre-Revolutionary War cannon ended up embedded in a sidewalk. According to Sykes, in the 1850s, the cannons from the fort were sent to the John Hill Foundry on Third Street to be melted down for sugar house machinery. However, the foundry returned the cannons to the city to be embedded into street corners to keep vehicles off the sidewalks. If you look at old photographs of downtown Baton Rouge, you'll see some of these cannons.

In the 1960s, the Department of Public Works removed all of the cannons except for the one at Third Street and Laurel. This particular cannon was saved in 1969 by local residents when it was slated for removal during street reconstruction.

Isn’t it interesting that many people who work in downtown Baton Rouge walk past a historical artifact dating back to the Revolutionary War every day, likely without even noticing it?

Check Out:

No comments:

Post a Comment